Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy was effective at producing “large, rapid, and sustained antidepressant effects in patients with major depressive disorder,” U.S. researchers report based on their recent randomized clinical trial.

They emphasized that their findings are consistent with the results of research over the past decade into psilocybin-assisted therapy’s antidepressant effects among patients with cancer who had psychological distress and among patients with treatment-resistant depression.

“Consistent with these previous studies,” the authors wrote,

the current trial showed that psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type, personally meaningful, and insightful experiences were associated with decreases in depression at 4 weeks.”

The report also notes other research over the past decade that has shown psilocybin to have “low potential for addiction and a minimal adverse event profile.”

The report appeared online on Nov. 4 in JAMA Psychiatry.

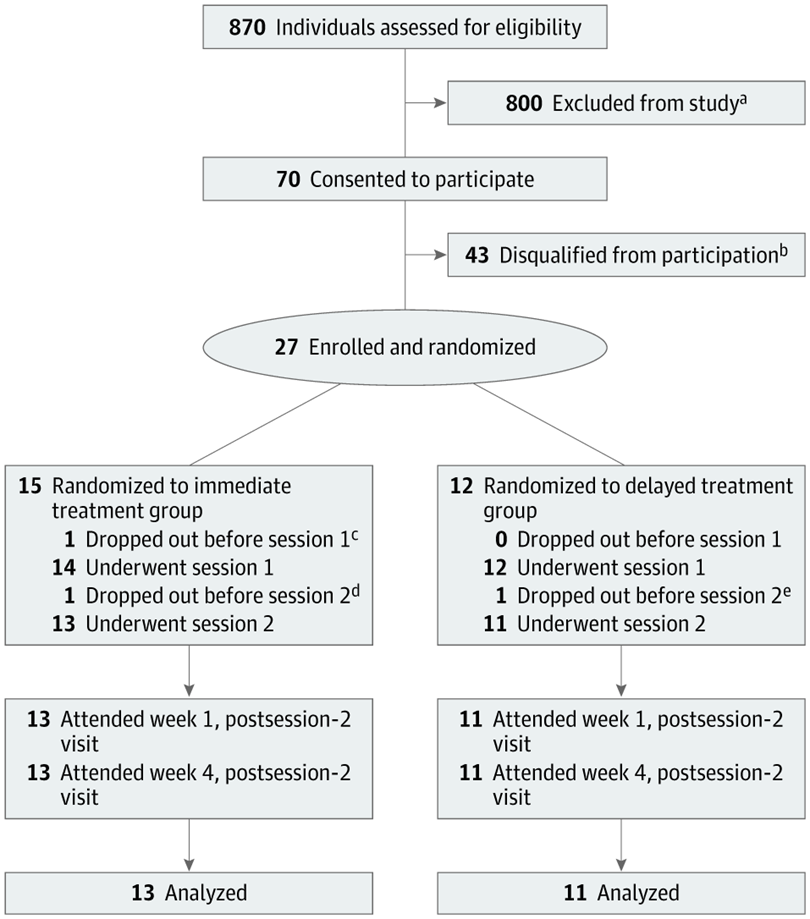

All 24 participants (mean age 39, 16 women) had been diagnosed with moderate or severe major depressive disorder (MDD), and at entry into the study none were taking medication for depression. Treatment lasted eight weeks and encompassed at least 16 in-person visits, in addition to two psilocybin sessions, typically about 10 days apart.

The participants were randomized to either immediate or delayed treatment. While the former group underwent the study intervention, the latter group was monitored weekly, in person or by phone.

This two-arm format allowed the delayed-treatment group to be a control group for the immediate-treatment group, letting the researchers differentiate effects of the psilocybin intervention from spontaneous symptom improvement, corresponding author Alan K Davis, Ph.D., assistant professor in the College of Social Work at Ohio State University, Columbus, told eHealthcare Solutions.

Each day-long psilocybin session included two facilitators remaining with the participant, who lay on a couch while wearing eyeshades and headphones. A nearly eight-hour music playlist assembled for these sessions included Vivaldi, jazz flutist Paul Horn, J.S. Bach, Brahms, Mozart, Samuel Barber, and Sir Edward Elgar.

The first psilocybin dose was 20mg/70kg, considered moderately high, and that in the second session was 30mg/70kg, considered high. Dr. Davis explained, “We wanted to start off with an initial dose that may give participants a chance to experience psilocybin effects with less risk for anxiety prior to giving them a high dose of the drug. In part this also allowed us to see whether there were changes in depression after the lower dose, to better gauge what dose is needed in future studies.”

Depression severity was assessed via the GRID-Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (GRID-HAMD), scored at baseline and at weeks 1 and 4 for the immediate-treatment group and weeks 5 and 8 for the delayed-treatment group.

The researchers found a clinically significant antidepressant response (50% or greater reduction in GRID-HAMD score) that persisted for at least four weeks, with 71% of participants continuing to show that response at week 4 of follow-up.

In an accompanying editorial, Charles F. Reynolds III, M.D., of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, commended the study’s rigorous methods, including steps taken to avoid experimental bias, “attention to efficacy and tolerability [and] high rates of retention, treatment completion, and follow-up.” The result, he concluded, is that “the data from this trial are clinically informative and have heuristic value for further research.”

Reynolds also, however, noted several issues (some unavoidable) with the research, including expectancy effects, questions around which patients are best suited for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, and uncertainty about how such therapy fits into acute and long-term care for depressive illness.

As to the latter, Dr. Davis noted that the authors are following up with study participants for 12 months after completion of treatment to examine this question and eventually report those findings.

Robin Carhart-Harris, Ph.D., head of the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, told eHealthcare Solutions,

This study adds more supportive evidence of the safety and efficacy of psilocybin therapy for depression.”

He noted the randomized components of this trial and the use of blinded assessment of symptom severity and praised the use of “gold standard assessments of depressive symptom severity.”

Although Dr. Carhart-Harris acknowledged that it’s “nigh-on impossible” to effectively blind a psilocybin study, he expressed hope that such an approach could be found, perhaps using active placebos. “Controlling for the psychological and psychotherapeutic components of the treatment seems especially important, as their role in determining outcomes are likely to be considerable.”

Dr. Carhart-Harris concluded that “the results are clinically meaningful according to standards for interpreting scores on these relevant scales. The improvements in depressive symptom severity appeared rapidly and were of a large magnitude, relative to conventional treatments.”

Simon B. Goldberg, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Counseling Psychology at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, said that to his knowledge,

this is the first randomized controlled trial testing psilocybin as a treatment for major depression.”

Its results, he continued, “add to a growing body of evidence that psychedelics, including but not limited to psilocybin, may induce rapid and sustained decreases in psychological symptoms including depressive symptoms.”

The use of a randomized design, Dr. Goldberg said, “provides much stronger causal evidence than previous studies that were conducted without a control condition. One of the most striking and clinically relevant features is the magnitude of the decreases, which are considerably larger than those typically achieved by a similar amount of behavioral treatment alone.”

Neither Dr. Carhart-Harris nor Dr. Goldberg was involved with the study by Davis, et al.

This study was funded in part by a crowd-sourced campaign organized by Tim Ferriss; a grant from the Riverstyx Foundation; and grants from Tim Ferriss, Matt Mullenweg, Craig Nerenberg, Blake Mycoskie, and the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Foundation. All eight authors are affiliated with the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, which is funded by the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Foundation and has received support from Mssrs. Ferriss, Mullenweg, Nerenberg, and Mycoskie. Dr. Davis and three co-authors received a total of three grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Davis is a board member at Source Research Foundation. A second author reported grants from Heffter Research Institute outside this study and personal fees as a consultant and/or advisory board member from Beckley Psychedelics Ltd., Entheogen Biomedical Corp., Field Trip Psychedelics Inc., Mind Medicine Inc., and Otsuka Pharmaceutical. A third author is a board member at Heffter Research Institute and received grants from it outside this study.

Davis, et al <https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285>

Reynolds <https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2772628>